Our top priority for your pet's surgery is to keep them safe and happy.

We use state-of-the-art surgical equipment and prioritize educating our clients, so you know the appropriate aftercare for your pet.

Common Soft Tissue Surgeries

Sometimes when we receive the news that our pet has life threatening abdominal or lung disease, we fear there is no treatment option. However, all of our veterinarians are experienced in procedures that may enable your pet to live a normal quality of life. Abdominal and soft tissue surgeries are regularly performed at Veazie Veterinary Clinic. Each veterinarian contributes their own specialized knowledge and training to our various surgical procedures.

Our animal hospital serves all of Northern Maine, including the Bangor and Orono areas. Our veterinarians are experts in advanced surgeries such as Tibial Tuberosity Advancement (TTA), Tibial Plateau Leveling Osteotomy (TPLO), Gastropexy, and more. If you are looking for a surgical expert for your pet in Northern Maine, give us a call today at 207-941-8840.

Spaying & Neutering

Mass Removal

Laceration Repair

Ocular Procedures

Emergency Surgery

Lung Lobe Removal

Exploratory Surgery

Foreign Body Removal

Anal Gland Removal

Thyroidectomy

More about Soft Tissue Surgeries

C-Section

Cesarean sections are performed by several of our doctors. Cesarean delivery is the delivery of a fetus by surgical incision.

Why Deliver By Cesarean?

Sometimes puppies or kittens are not able to be delivered naturally. This can be due to the size of the pups or kittens, the mother’s pelvic size or shape, or the fetus could be poorly positioned. It may also be required in the case of uterine inertia, when there is little or no contractions in the uterus, or if there are signs of fetal distress such as black, red or green discharge.

A C-section should not be performed until the dam is overdue, and it is best to wait until labor starts, or the temperature drops below 99° Fahrenheit and stays low. We may also run a test to look at the mother’s progesterone levels to see if the puppies are truly ready to be delivered or whether there is another issue that needs to be addressed.

Dr. Keene heads up our reproduction program and would be happy to answer any additional questions about C-sections or breeding in general. You can also check out our breeding pages for information on everything from services we offer, to common questions.

Diaphragmatic Hernia Repair

The diaphragm is the muscle that separates the chest (thorax) and abdomen. When the diaphragm is disrupted it allows abdominal organs to migrate into the chest cavity. Most dogs and cats who have this have experienced some sort of trauma or stress like being hit by a car.

As you can see in this normal chest radiograph the diaphragm creates a clear separation between the lungs (darker mottled area) and the abdomen (the whiter portion to the right of the film).

In this abnormal radiograph of a cat with a diaphragmatic hernia you can see the area of the lungs to the left of the picture are blocked with a white hue. This white hue is abdominal organs that have moved into the chest cavity.

How do you repair it?

Surgery needs to be performed as soon as the patient is stable. The diaphragmatic hernia is usually repaired through the abdomen resituating organs where they belong and suturing the diaphragm in the correct position. A chest tube will also be placed to remove air and any fluid that may accumulate. Once the chest tube is removed the pet can go home. It is important they stay quiet and avoid activity during the post-operative period.

Laryngeal Paralysis

Laryngeal Paralysis is a slowly developing disease. The muscles that cause the larynx to open and close simply no longer work. This condition is more common in larger breed dogs and typically starts to become a problem as they age towards their senior years.

What does the Larynx do?

The larynx (voice box) is located in the throat. We know that it is what gives animals the ability to vocalize, but it is also the cap of respiratory tubing. The larynx closes the respiratory tract off while we eat and drink, so we don’t inhale our food. When you take a deep breath, the folds open directing air in.

What are signs of Laryngeal Paralysis?

Laryngeal paralysis is slow acting. It can affect one or both sides of the larynx. Eventually it will progress to the point that the muscle can no longer open and the larynx flaps weakly. When it has progressed to this stage the dog can no longer take a deep breath. This can lead to anxiety and rapid breathing and distress. A respiratory crisis can occur from the partial obstruction creating an emergency and even death. Early warning signs include:

- Excess panting

- Exercise intolerance

- Voice Change

- Loud Breathing Sounds

- Respiratory gasping or distress.

Laryngeal Paralysis Treatments

The only treatment options are surgical. There are two main surgeries to treat it that we perform at Veazie Veterinary Clinic. Based on the severity of the problem the veterinarian will discuss with you which is best.

Laryngeal Tieback (Lateralization Surgery)

This is the most commonly performed surgery for laryngeal paralysis. In this surgery a couple of sutures are placed to pull one of the cartilages backward in an open position.

The chief complication is that the cartilage only needs to be move a few millimeters and if opened too far the larynx cannot properly close and aspiration pneumonia becomes a greater risk. These patients often have a persistent cough after eating or drinking.

De-Barking (Ventriculocordectomy)

The de-barking surgery is generally thought of as a surgical solution to a dog that barks excessively. However, it is also a possible treatment for laryngeal paralysis. The surgery removes the vocal folds, removing the patient’s voice to a whisper. The hole created in the absence of the vocal fold makes a larger airway opening and is generally large enough to relieve obstruction.

Complications include swelling and bleeding (which can cause obstructions in themselves); regrowth of webbing or vocal tissue can also occur. For this reason this technique is rarely used.

Soft Palate Resection

What is an elongated soft palate?

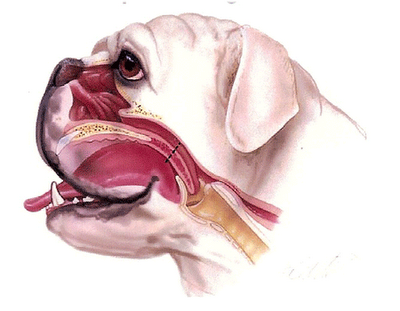

The soft palate is the back of the roof of your mouth. In short headed (brachycephalic) dogs their lower jaw is in proportion with their body, but the upper portion has been shortened. Because their face is squished, in some dogs the soft palate extends too far into the back of the throat and partially obstructs the airway when breathing in.

Signs and symptoms:

- History of noisy breathing

- Retching or gagging especially while swallowing

- Exercise intolerance

- Blue gums/cyanosis (lack of oxygen)

- Occasional collapse especially after activity/excitement/excessive heat

Dogs with brachycephalic syndrome are at greatest risk for heat stroke because they can not pant properly to cool down. To fix an elongated soft palate, the surgeon will remove the excess portion and place dissolvable sutures.

Splenectomy

The spleen is an oblong organ just below the stomach. A pet can live a completely normal life without a spleen, however the spleen is a storage area for blood. If a pet had a severe hemorrhage, for example, the involuntary muscles of the spleen contract, squirting forth a fresh supply of blood. The spleen also removes old red blood cells from circulation.

When would you need to remove the spleen?

There are three major reasons to remove the spleen. The first is a mass on the spleen. Masses can be benign or malignant. It is not always clear prior to surgery. Sometimes the veterinarian may check to see if cancer has spread to the lungs with an x-ray to determine if it is malignant, but lack of evidence does not mean its benign.

A second reason for removal is bloat. When the stomach twists in bloat it can cut of circulation, but it also can twist involving the spleen. Frequently the spleen is damaged and must be removed in part or fully.

The third reason is traumatic rupture. If the patient has had blunt force trauma to the abdomen such as being hit by a car or kicked by livestock the spleen may rupture. It can bleed dangerously. If a tear in the spleen is small it may be repaired. However, if it is severe it needs to be removed.

Stenotic Nares

The short faces of Pugs, Boston Terriers, Pekingese, Boxers, Bulldogs and other breeds are cute, but can cause problems. It’s called brachycephalic (short head) syndrome. Essentially years of breeding have compacted the anatomy of the nose and mouth of these breeds into a smaller area making it difficult for them to breathe.

What Are Stenotic Nares?

Stenotic nares is a fancy term for narrowed nostrils. In breeds with short heads, the nasal passage opening is abnormally narrow. If it is severe, then it needs surgical correction to help the dog breathe normally. Think of trying to breath through a coffee stirrer vs. a large straw. In this procedure, the surgeon simply makes a small incision in the nostril and sutures it into a more open position.

Risk Reduction

Although many technological advancements have made anesthesia and surgery very safe for pets, some risks still exist. To decrease these risks, we require all patients undergo a physical exam prior to surgery and also conduct a pre-anesthetic blood screening before surgery day. This blood panel will help reduce anesthetic risks by ruling out many internal problems, including clotting disorders, liver and kidney abnormalities and anemia. In addition to the examination and blood screening, we also place an intravenous catheter and administer fluids to help keep your pet hydrated and maintain blood pressure during the procedure.

Anesthesia Safety

Anesthetic Safety is the cornerstone to every surgery. The ultimate safety is to minimize anesthetic time, which we do by having the surgery suite and surgeon ready and waiting for the patient so there is no wasted anesthetic time. The doctors and staff at the Veazie Veterinary Clinic want to provide the safest anesthesia, least stress and minimal pain for your pet’s procedure. The following information will assist you in understanding how we will care for your pet.

What precautions are taken when using anesthesia?

Pre-anesthetic evaluation

Every patient is evaluated by a doctor for anesthetic risks and to clarify the procedure being performed. This physical evaluation is thorough. Not only will the vet listen to your pet’s heart and lungs, but also palpate their abdomen, palpate for pulses, check lymph nodes and other indicators to ensure your pet is healthy for anesthesia.

Preoperative blood work

A preoperative blood sample is drawn and tested to evaluate kidney and liver function, blood sugar and protein levels. It also checks hematology (red and white blood cell levels). This ensures that there is no presence of anemia or infection.

Intravenous catheter and fluids

An intravenous catheter is placed in all surgical patients. This not only ensures access to a vein in case we need to supply drugs or reverse injectable anesthetic agents but also allows us to administer fluids during the procedure.

Fluids help maintain adequate blood pressure and blood flow to vital organs during surgery. We can also put pain medicine in the fluids to help onboard pain control for a smoother recovery.

Intubation

Each animal under anesthesia is intubated by a trained technician. Intubation allows us to ensure an open air pathway, increase the amount of oxygen a patient is getting.

In addition, intubation reduces the risk of leaking inhaled anesthetic agents, keeping our staff safe.

Anesthetic monitoring

We use state of the art monitoring equipment including an ECG, pulse oximeter (blood pressure monitor), & thermometer to know exactly how your pet is doing. Although accurate equipment is important, the technician running it is the key to safety.

Our techs are trained in anesthetic monitoring and watch your pet from induction to recovery.

Anesthesia & Pain Control

Anesthesia has come along way from what it used to be. Its far more safe and controlled. Inhaled gas is minimized by the use of other injectable – and in some cases reversible – agents, as well as pain medication with sedative effects.

Veterinarians anesthetize animals on a daily basis, but when it comes to your own pets, owners often are nervous about the risks. Modern anesthesia is very safe. According to Veterinary Partners the risk of a pet dying under anesthesia is less than 1%. This is in part because of advances made in monitoring and the drugs available. Unfortunately, there is no “standard” for anesthesia in the veterinary world. We encourage you to ask the veterinarian performing the surgery what they do to minimize anesthetic risk before choosing a surgeon.

Anesthetic Agents

Today inhaled anesthetics are far safer than older anesthetics. Inhalant agents are anesthetic drugs that are breathed in and out, rather than injected into blood vessels or muscle. The drugs are absorbed through lung tissue into the blood vessels and circulate through the body. Sevoflurane is a newer anesthetic gas that is less likely to aggravate pre-existing abnormal heart rhythm. Additionally, it enters and exits the brain rapidly. This allows for greater control of “depth” of sleep and a faster recovery.

The perfect anesthetic drug would not alter heart or lung function, provide adequate pain control and excellent muscle relation and is readily reversible. The perfect drug does not exist. However, by using a combination of drugs we can get close. Pets are pre-medicated with a pain medication that is also a sedative and muscle relaxant. Alfaxan is then used as a short- and fast-acting anesthetic to induce sleep. Sevoflurane is then used to maintain unconsciousness. In this way, we can minimize the side effect of any one agent by using less of it.

Pain Control and Anesthetic Safety

Effective pain control is the other way to minimize the use of anesthesia. Surgery is painful and painful events are more likely to awaken a patient. By minimizing pain we can use less anesthesia and keep the patient “lighter” under anesthesia. To control pain we use nerve blocks whenever appropriate. We add pain control to the pet’s fluids that run during surgery, and as mentioned prior, one of the pre-anesthetic agents helps with pain control and sedation. We also give additional oral pain medications to continue pain control at home.

Laser Surgery

At Veazie Vet as many surgeries as possible are conducted using a C02 laser. Using laser for surgical procedures reduces bleeding, pain, and swelling at the surgery site.

Benefits to using a Laser

- Less Bleeding: As it cuts, the laser seals small blood vessels. This drastic reduction in bleeding enables a number of new surgical procedures that are not practical with conventional scalpel.

- Less Pain: The CO2 laser beam seals nerve endings and lymphatics, resulting in less edema and pain. The patient experiences a far more comfortable post-operative recovery.

- Reduced risk of infection: This is one of the unique features of the CO2 laser beam. It efficiently kills bacteria in its path, producing a sterilizing effect.

- Quicker recovery time: Reduced risk of infection, less bleeding, less pain and less swelling often allow the patient a far quicker recovery after the surgery.

What is a C02 Laser?

LASER is an acronym for Light Amplification by Stimulated Emission of Radiation. So, a laser is a device that produces concentrated light rays. Interaction of laser light with the water in tissue can either vaporize or chip away causing an incision. The beam is highly focused and efficient and at the same time it is “cutting” it is also sealing capillaries, small blood vessels, and nerve endings. As compared to conventional methods, laser surgery damages less tissue and reduces blood loss and pain sensation. This all leads to a faster healing time and more comfortable patient.

Orthopedics

Orthopedics is a branch of medicine that deals with the prevention or correction of injuries or disorders of the skeletal system and associated muscles, joints, and ligaments.

Dr. Cloutier has a special interest in orthopedics and orthopedic surgeries. We regularly accept referrals from veterinarians from across Maine and even into neighboring states and Canada. Dr. Cloutier is well versed in ligament injuries, as well as fractures and dislocations. We work with medication, physical therapy, and when needed, surgical avenues to restore your pet to their favorite activities.

What is Fracture Repair?

A fracture simply refers to any break or crack in a bone. Each type of fracture has its own possible methods of repair. Splinting generally does not provide sufficient support and surgery is required to place hardware to allow healing.

Types of Fractures & Other Orthopedic Injuries:

- Closed Fracture: Fractures in which there is no related external wound.

- Open (formerly known as compound) Fracture: Fractures associated directly with open wounds (the bone may or may not be visible through the wound).

- Dislocation: An injury to the connective tissues holding a joint in position that results in displacement of a bone at the joint.

- Sprain: An injury to a joint, ligament, or tendon in the region of a joint. It involves partial tearing or stretching of these structures without dislocation or fracture.

Other types of orthopedic injuries can involve torn ligaments, particularly in the knee. Many athletic, large breed dogs will tear the cranial cruciate ligament in their knee, which results in a sudden loss of use of the leg, along with joint pain and swelling in the knee. Surgical stabilization is the best means to repair this injury.

Surgery

If surgery is recommended, it will involve the application of one or more metal surgical implants, such as pins, wires, plates, or screws.

The primary goal of fracture fixation surgeries is to restore broken bones to their original anatomic position and rigidly fix them in place while healing occurs.

In some cases, the fracture may be too severe to permit perfect anatomic restoration of all pieces, but there will still usually be a way of providing stability to the fractured bone and to allow use of the limb during the healing period.

What is Cruciate Ligament Disease?

The Knee Joint Anatomy Consists of:

- The femur above

- The tibia below

- The kneecap (or patella) in front

- Two small bones called the fabellae behind.

- A figure eight cartilage cushion called the meniscus between the bones

- Several ligaments that keep the joint in alignment

There are two cruciate ligaments that cross inside the knee joint: the cranial and the caudal. The cranial cruciate prevents the tibia from slipping forward. This is the ligament that most commonly fails.

Diagnosing Cranial Cruciate Disease:

The diagnosis is made by palpation of the joint.

- Effusion (fluid) can be felt in the initial stages

- Thickening of the joint

- Instability known as the cranial drawer sign

- Long term cruciate injury may result in a knot on the inside surface (medial buttress)

- Nervous dogs may tighten their muscles during the exam, requiring sedation to accurately palpate the drawer sign.

- Radiographs will rule out any other orthopedic conditions that may be involved.

Why Does the Cruciate Ligament Fail?

There are two types of ligament failure. Some young healthy dogs exert excessive force on the ligament and cause it to fail. This is usually a very sudden lameness in a young large breed dog.

The other group is an older large breed dog, especially if overweight, that has a slow weakening and eventual failure of the ligament. There is not a significant injury the causes this group of dogs to become lame, often just stepping down off the bed or a small jump can be all it takes to break the ligament.

Unfortunately one third of larger, overweight dogs that rupture one cruciate ligament will rupture the other one within a year’s time.

Meniscal Injury

The instability that results from a failed cruciate ligament can result in damage to the meniscus. The meniscus is a cartilaginous cushion that helps to distribute forces in the knee. When the knee becomes unstable the meniscus can become torn or damaged.

Dogs with meniscal damage may have an audible clicking sound when they walk or when the knee is examined, but for a definitive diagnosis the meniscus must be inspected at the time of surgery.

If the meniscus is damaged it will be removed at the time of surgery. A new meniscus will regenerate out of fibrocartilage. If a torn meniscus is not removed the joint may continue to be painful.

Cruciate Ligament Surgical Options

Several different surgical repair techniques are used in veterinary medicine today to repair cruciate ligaments. The three most common are a Lateral Suture Ligament Replacement (extracapsular repair), Tibial Plateau Leveling Osteotomy (TPLO) and Tibial Tuberosity Advancement Surgery (TTA). All three surgeries have their advantages. Please call us at 207-941-8840 to set up a time to meet with one of our veterinarians to discuss the best option for your pet.

Extracapsular Repair

During this procedure:

- The joint is opened and inspected for damage

- The torn ligament is removed

- Arthritic changes may be removed

- The meniscus is inspected and removed if necessary

- The joint is stabilized by replacing the failed ligament with one or more nylon bands

- These bands will provide stability but can give and flex as needed to allow for mobility. The bands normally remain in place for life.

This surgery is done routinely at the Veazie Veterinary Clinic. We perform a thorough evaluation prior to surgery to be certain this procedure is necessary and appropriate for your dog.

- A pre-surgical evaluation including blood work and radiographs will be done

- An IV catheter, fluids, pain medication, antibiotics will be administered

- Our rehabilitation technicians will perform post-operative care and rehab

- We will provide you with all medications, icepacks, and instructions to ensure your dog have the best outcome possible.

Tibial Plateau Leveling Osteotomy (TPLO) in Northern Maine

The TPLO is a new procedure that must be performed by a veterinarian licensed to perform this surgery. This surgery is complex and involves special training in this specific technique. We recommend that this procedure be performed by surgeon experienced in the technique, like our Veazie Veterinarians.

- Several radiographs are necessary to calculate the angle of the cut in the tibia

- The joint is opened and inspected for damage

- The torn ligament is removed, arthritic changes may be removed

- The meniscus is inspected and removed if necessary

- The tibia is cut and rotated until the sloped tibial plateau is perpendicular to the line between the stifle and the hock joint centers.

- Once in a neutral position, the need for a cruciate ligament is eliminated.

Dr. Mark House is a boarded veterinary surgeon that travels from clinic to clinic to do specialized surgeries. Dr. House currently does surgery here once a month and regularly performs TPLOs here for our patients.

Tibial Tuberosity Advancement Surgery (TTA) in Northern Maine

The forces within the knee are very complicated and change as the knee is rotated through its range of motion. In a normal standing position there is a tendency for the lower end of the femur to slide backwards on the tilted tibial plateau, this is called tibial thrust. This force can be corrected by counteracting this force by changing the angle of pull of the very strong patellar tendon by advancing the tibial tuberosity (TTA).

- In this technique, the front edge of the tibia is cut

- A titanium wedge is placed between the body of the bone and the tuberosity

- This movement changes the angle of the patella ligament to the stifle

- In turn, this neutralizes the shear forces and eliminates the problem in the joint.

This surgery is the most common repair of cruciate ligaments that we do here. Dr. Cloutier regularly performs these procedures for dogs of all sizes.

What if the Rupture Isn’t Discovered for Years and Joint Disease is Already Advanced?

A dog with arthritis pain from an old cruciate rupture may still benefit from surgery. Some of the arthritic changes can be removed. If the meniscus is damaged it should be removed and the joint stabilized.

What if the Cruciate Rupture is Not Surgically Repaired?

Without an intact cruciate ligament, the knee is unstable causing premature wear of the cartilage. Degenerative joint disease occurs causing chronic pain and loss of motion. This process can be slowed or arrested by surgery but cannot be reversed.

What is Patella Tendon Disease?

A trick knee or dislocating kneecap is really a medial luxating patella. This is a common problem in toy and small breed dogs. However, it may occur in large breed dogs as well . The characteristic lameness is a little skip in your pet’s step but can be as severe as running on three legs. However, unlike a torn cruciate the dog will suddenly recover as if nothing had happened.

Knee Joint Anatomy Consists of:

- The femur above

- The tibia below

- The kneecap (or patella) in front

- Two small bones called the fabellae behind.

- A figure eight cartilage cushion called the meniscus between the bones

- Several ligaments that keep the joint in alignment

When the patella luxates, the kneecap (patella) has slipped out of the smooth grove that it normally rests in and glides up and down in. When the kneecap dislocated, the knee cannot fully extend correctly and stays bent.

Hopefully they can return the kneecap to normal position, but if the kneecap luxates routinely, over time the friction wears the grove flattening it. In these cases, surgery is required to repair the joint.

Which dogs need surgery?

Patella luxation is graded on a system of 1 to 4 based on severity and how much time the kneecap is out of position:

Grade 1: With manual manipulation the kneecap can be moved out of the grove, but when the manipulation is removed it falls back into place.

Grade 2: The kneecap can be moved out the grove with manual manipulation, but this time the kneecap does not return to normal position when the manipulator lets go. Surgery is beneficial for these dogs as arthritis and further damage to the knee can develop over time.

Grade 3: The patella is consistently out of place , but can be replaced with manipulation to its normal position. However, without manipulation the kneecap will not stay in place. Surgery is recommended to return to normal function.

Grade 4: The patella may always be out of place, and the bone is sufficiently worn down so that it can not be replaced in the grove even with manipulation. In these cases dogs have difficulty extending the knee and walks with bent knees almost all the time. surgery is necessary to return normal function.

Patella Tendon Surgery Options

Lateral Imbrication (Lateral Reinforcement)

This involves tightening the joint capsule. As the kneecap slips in and out of place the joint capsule that surrounds it is stretched. The surgeon simply takes a tuck in the joint capsule so that the kneecap is better confined.

Although this may be sufficient in very mild cases, in most cases this is done in addition to other surgical modifications, ensuring that the kneecap does not continue to slide in and out of place and enlarge the joint capsule again in the future.

Trochlear Modification

The patella rests in the trochlear notch at the base of the femur. In a correctly functioning joint, the patella slides up and down this groove as the knee bends. In an abnormal joint, the walls on either side of the trochlear notch are flattened, allowing the patella to move out of this notch and to either side of the knee.

In a trochlear modification surgery, the surgeon deepens the groove so the patella stays where it belongs. The cartilage that lines the notch is peeled away from the bone, the groove deepened and the cartilage replaced.

Tibial Crest Transposition:

Tibial crest transposition surgery is required in extreme cases, where long term, severely displaced kneecaps have resulted in a knock-kneed conformation. In these cases, the patella rests outside of the trochlear notch so frequently that it has caused the tibias to rotate.

The rotation is actually due to the thigh muscle (the quadriceps pictured to the left) attaching inwardly. In this case, the tibial crest will have to be removed (where the quadriceps attach) and pinned back where it belongs to straighten out the leg.

What is Hip Dislocation?

Hip dislocation is usually a result of trauma that dislocates the ball from the socket – also referred to as hip luxation. In order for the hip to luxate the trauma must have been significant to rupture the capital ligament. The femur almost always luxates the same way; up and forward.

The most obvious symptom is when the patient is not bearing weight on the affected leg, however a radiograph will help confirm if the joint is dislocated. If the luxation is not corrected, scarring and fibrous attachments can create a false joint.

Repairing a Hip Luxation

The dislocation is repaired by closed reduction. This is means that the luxation is corrected by sliding the ball of the femur back into the socket manually without a surgical incision.

If the hip appears to be normal other than the luxation and occurred within three days, this is the most common solution. If the injury happened longer than three days ago, muscle contraction makes successful reduction very challenging.

Other complications, such as damage to the femoral head or pelvis, will require surgical repair.

Surgical Repair

Surgical techniques vary and depend on damage. Optimally, the hip is able to be reduced and only a small tear in the joint capsule must be repaired with suture.

In some cases, the joint capsule is too damaged, resulting in the need to places screws around the acetabulum, and a hole drilled to it keep the joint in place.

Post Surgery

After surgery, most orthopedic patients have several recheck appointments, many of which include therapy and rehabilitation. The rehabilitation is conducted at the Wellness Center and can help reduce healing time, pain, stiffness and arthritis while also increasing range of motion.

What to Expect After Orthopedic Surgery

Our number one priority is to return your pet to their favorite activities as quickly as possible. We work with the owner and pet to create both a pain control regimen, and develop a rehabilitation plan that will restore joint health and function.

Pain Control

Post-surgically your pet will be in some pain for the first few weeks of the healing process. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs NSAIDs are extremely valuable in human and veterinary medicine as pain relievers.

Joint Health

We approach joint health from two angles. First is restoring the joint capsule. A joint consists of articulating bones, a fibrous capsule enclosing the joint, and a slippery lubricating joint fluid to facilitate the gliding of the two bones across each other as the joint is flexed. The bones are capped by cushions of cartilage to facilitate frictionless gliding. This system is disrupted by the surgery and in some cases we recommend Adequan injections or Omega 3 supplements to support joint health.

The other way to restore joint health and mobility is through rehabilitation. Our technicians Heather and Bobbie have extensive education on the topic and will work with you to design a program that will get you pet out running and playing again; in many cases within 6 weeks.

Pain Management (NSAIDs)

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are extremely valuable in human and veterinary medicine as pain relievers.

Most human drugs in this class should not be given to pets due to undesirable side effects, some of which can be life threatening. Always seek the advice of your veterinarian before giving your pet a new medication.

Human NSAIDs

- Aspirin

- Ibuprofen (Advil or Motrin)

- Acetaminophen (Tylenol)

- Naproxen (Aleve)

Veterinary NSAIDs

- Carprofen (Rimadyl)

- Deracoxib (Deramaxx)

- Meloxicam (Metacam)

- Galliprant (grapiprant)

Given wisely and with appropriate monitoring, NSAIDs have the potential to significantly improve our pets’ quality of life. At the current time, these drugs are only approved for use in dogs since cats cannot tolerate most drugs in this class. (Meloxicam may be the exception, but its use in cats is off-label and it must be used with caution.)

Note: While there is some concern in human medicine about the risk of heart attack or stroke with the use of COX-2 inhibitors, (such as Celebrex and Vioxx), to date there is no evidence of a similar concern with dogs. Deramaxx is currently the only selective COX-2 inhibitor used in dogs. As a species, dogs are not prone to the same types of cardiac disease as humans, and there have been no reports of these types of adverse effects on dogs.

When Are NSAIDs Used?

- Commonly given to control pain associated with arthritis

- May be used in any number of situations where inflammation leads to pain

- Short term control of pain following surgery or injury

- Long term control of chronic pain such as arthritis

In Long Term NSAID Use:

- A baseline blood panel should be performed to ensure there is no evidence of underlying liver or kidney problems

- The liver is the primary organ involved in metabolism of these drugs

- Changes in dose or drug may be needed if the liver is compromised

- Monitoring liver and kidney values periodically is recommended

- The kidneys can be adversely affected if already compromised, requiring different type of pain reliever be used

Possible Side Effects

A range of adverse effects are possible, from a mild upset stomach to more serious organ problems, and you should monitor your pet closely for:

- Decreased appetite or refusal to eat

- Vomiting or diarrhea (especially with blood)

- Depression or lethargy

Symptoms may especially occur within the first 3-4 weeks of administration. If your pet shows any of these signs after starting medication, discontinue use of the drug and call the office. Chances are that your pet is just experiencing some mild stomach upset (which can often be avoided by giving the drug on a full stomach), but it is best to be cautious if these signs are observed.

Avoiding Drug Interactions

NSAID side effects are far more common if more than one type (i.e.: aspirin and Rimadyl, Deramaxx and Metacam, etc.) are given simultaneously, or if given with a steroid such as prednisone or dexamethasone.

For this reason, it is very important to tell your veterinarian if your pet is taking any other medication or if your pet has had significant side effects from any other drugs, even medications taken for other reasons.

Some dogs that do not appear to be helped by one NSAID may respond to another, so a change from one to another may be necessary. A rest or ‘washout’ period is needed in this case, to avoid possible side effects. This period may range from 3-10 days, depending on the drugs involved. Switching from aspirin to another NSAID requires the longest washout period. Do not give your dog any medication of this class without consulting your veterinarian first.

NSAIDs, like any other drug, carry the small possibility of side effects, but overall, they have been of great value in maintaining a good quality of life, particularly in our aging pets. Please ask your veterinarian if you have any questions about your pet’s current medications.

Joint Therapy/Adequan®

The Joint Anatomy Consists of:

- Articulating bones

- A fibrous capsule enclosing the joint

- A slippery lubricating joint fluid to facilitate joint motion

- Cushions of cartilage to facilitate frictionless gliding

Cartilage consists of what is called matrix, which makes up 95% of cartilage. Chondrocytes secrete matrix and make up the other 5% of cartilage material. Cartilage matrix consists of tough, structural fibers called collagen.

Proteoglycans soak up water and create a cushion similar to a waterbed, which helps to absorb the pressure exerted on the joint as it works. The proteoglycan molecule looks something like a bottle brush: it has a long handle (the “proteo” part) and the long bristles called glycosaminoglycans (or GAGs) that soak up the water.

Over the years, through either injury or poor conformation, cartilage wears down or is damaged, and arthritis results. The body must then make more matrixes and will require the raw materials to do so. Polysulfated GAGs may be injected into the body, where they will be distributed to any joints currently undergoing cartilage repair.

It turns out that polysulfated GAGs represent more than just building materials. They have anti-inflammatory properties of their own, which help slow down the actual damage to the cartilage. Beyond simply making more matrixes, they promote enzyme systems that facilitate other aspects of joint repair and help the joint create more lubricating fluid.

ADEQUAN® INJECTIONS

Adequan® is a polysulfated glycosaminoglycan.

- Adequan® is given as an injection and so is able to reach all joints but it seems to have a special affinity for damaged joints.

- Adequan® should be avoided in patients with blood clotting abnormalities as a matter of caution.

- Adequan® is best given as a series of injections, starting twice a week for a month, then once a week for a month, then every other week for a month and finally, once monthly.

- After an effect is seen, Adequan® injections are given on an as needed basis.

- Adequan® is formally approved for use in dogs and horses but may also be used in cats with good results.

- Adequan® may be combined with NSAIDs and with glucosamine and chondroitin sulfate.

Joint Supplements

Omega 3 Fatty Acids

Certain fats have been found to have anti-inflammatory properties. This finding has primarily been used in the treatment of itchy skin, but many arthritic dogs and cats have also benefited from fatty acid joint supplements.

While there are no toxic issues to be concerned with, these products require at least one month to build up to adequate amounts. Effects are not usually dramatic but can be helpful.

Omega 3 fatty acids can be used in dogs and cats.

Omega 3 fatty acids can be combined with other treatments.

Welactin® Canine – Softgel Caps

One Capsule Delivers:

- Total Omega 3 Fatty Acids: 300 mg

- Eicosapentaenoic Acid (EPA): 155 mg

- Docosahexaenoic Acid (DHA): 100 mg

Dosing: Give 1 capsule per 20 pounds of your dog’s body weight daily

Ingredients: Fish oil, gelatin, glycerin, water, natural peppermint oil and mixed tocopherols.

Welactin® Canine – Liquid

One 6ml Scoop Delivers:

- Total Omega 3 Fatty Acids: 1,450 mg

- Eicosapentaenoic Acid (EPA): 750 mg

- Docosahexaenoic Acid (DHA): 500 mg

Dosing:

- 5-9 lbs: ½ scoop every other day

- 10-19 lbs: ½ scoop daily

- 20-44 lbs: 1 scoop daily

- 45-79 lbs: 1 ½ scoops daily

- 8-114 lbs: 2 scoops daily

- Over 115 lbs: 2 1/2 scoops daily

Ingredients: Salmon oil, fish oil, mixed tocopherols, mono-and diglycerides, soybean oil, citric acid and rosemary extract.

Welactin® Feline – Softgel Caps

One Capsule Delivers:

- Total Omega 3 Fatty Acids: 250 mg

- Eicosapentaenoic Acid (EPA): 125 mg

- Docosahexaenoic Acid (DHA): 85 mg

Dosing: Give contents of one softgel capsule daily. Twist end of cap to open and squeeze contents directly onto food. (Do not feed gelatin capsule to your cat, administer contents of capsule only.)